By Shane Treadway

The moment I knew that the COVID-19 epidemic was legitimate was when NPR announced that the NBA was canceling the season. As Lead of Internationalization for a private K-12 school, I had been organizing three international trips since last summer. It quickly hit me that those trips would be abandoned. Travel fears and legislative ambiguities would most likely kill next year’s trips as well. So much for this very critical part of my job description. I’d have to make some serious adjustments.

Businesses and organizations of all types are facing similar dilemmas as travel screeches to a halt and employees retreat indefinitely to their living rooms. With so many unknowns, businesses are wondering, “How do we survive a crisis of this magnitude that we’ve never navigated before?” The answer: Develop and apply the core competency of cultural intelligence (CQ), one’s ability to succeed in unfamiliar intercultural contexts.

Firstly, the ability to communicate clearly and build trusting relationships across cultures is even more important in a quarantined, virtual world. Secondly, CQ is not only about “other” cultures, it is about understanding one’s own complex, diverse and rapidly shifting culture. Our current business environment demands speedy and agile pivoting that will take strong wills, keen observations, plenty of intentional interconnectedness and the quick modification and application of new ideas. All of these aptitudes will be vital for survival, and all are strengthened by increased cultural intelligence.

Don’t lose grasp of the importance of culture during the COVID-19 shift

Culture forms the building blocks of an individual’s and organization’s collective identity. It reflects the unique ways we make sense of the world. The tools that we use to express our experiences (mainly language, but there are infinite non-verbal nuances) and the canvasses upon which we express ourselves (mainly political, religious, organizational, educational and family structures) have been handed down to us. In short, culture refers to people’s shared understandings that are the result of shared experiences. In its most minimal form, culture is shared meaning.

Cultures can also be understood as unique systems of codes. These prefab codes help us simplify the process of organizing an enormity of experiential data and greatly increase efficiency in social interaction where codes are shared. On the flipside, confusion increases where they are not. Conflicting codes can’t communicate. And here lies the biggest hurdle for intercultural relationship building, intercultural communication, and, in our present COVID-19 context, cultural paradigm shifts.

“Organizations that employ or serve culturally diverse people must have a firm grasp on how culture develops and functions, even in “normal” times.”

Organizations that employ or serve culturally diverse people must have a firm grasp on how culture develops and functions, even in “normal” times. They need to learn how to discover the different systems of meaning of their stakeholders, interpret them, and organize that variation into an organizational language coherent across departments or international offices. Even organizations that employ from and serve one geographic area will benefit greatly by understanding the communicative gaps between subcultures related to gender, ethnicity, religion, sexual and political orientation. The degree to which these variations affect the perception of problems and solutions related to the coronavirus pandemic will determine an organization’s approach to pivoting to post-coronavirus norms. In the manual Culturally Competent Crisis Response, Silva and Klotz write, "While various levels of culture may overlap, they are not necessarily compatible and may result in conflict. Thus, what works in one culture may not work in the other, and the differences may lead to misunderstandings and conflicts."

Where shared meaning breaks down, human socialization can become stressed and divided. The breakdown of shared meaning comes through prolonged separation, where individuals from various backgrounds are no longer negotiating the meaning of an event or experience together. Obviously, quarantine separates, as does loss of employment and social distancing.

And at a time like this, when socioeconomic realities are in regular flux, stress is increased. People are unsure of their future and the broader community’s ability to take care of their needs. And when individuals pass through struggles in isolation, they will rely on their strongest cultural codes and nearest relations for answers and support. For many, these are likely not those of their organization. So, an important question becomes, how do businesses get at the cultural meanings relevant to their survival? Is it possible to discover and integrate the cultural components of their stakeholders that will be necessary to reconstruct relevant products and services?

This crash course in culture is important for navigating current COVID related shifts precisely because they are cultural shifts. Because of the radical and speedy nature of these shifts, they pose critical organizational challenges. Again, we are not only dealing with cultural variation across nationalities or competitive organizations, but with the diversities within our own context that are greatly complicated by these rapid shifts. Below, we will consider the most probable culturally related challenges for organizations navigating through COVID-19, and then look at how cultural intelligence lends heavily toward the creation of well-integrated solutions.

Cultural challenges related to COVID-19

Quick and frequent change

The coronavirus disruption came fast and furious. Typically, culture develops over long periods of time. A beneficial component of culture is the sense of normalcy and predictability it gives to communities, so they feel safe and in control of their environment. Rapid shifts complicate this. Similarly, organizational culture does not usually develop quickly. Members need time to adapt and integrate to unique insider language and ways of doing things. In times of quick disruption or catastrophe, organizations cannot rely on the natural development of culture. They must act quickly and attempt solutions to which the community will not have time to influence, digest and adapt. In as much as leaders or influential voices represent the demographic of key stakeholders, decisions will more likely resonate across the organization. To the degree that the culture of leaders differentiates from key stakeholders, communication success and decision relevance will decrease.

Culture shift can be traumatic

Research reveals that culture shift induces various levels of stress and trauma. One common type of culture shift includes regular interaction within multicultural social settings such as diverse school campuses and work environments or participation on multinational teams. Communicative, relational, and coping success are shown to decrease in diverse settings when not mitigated by cultural competency training.

The conditions for cultural trauma are exponentially enhanced when ‘normal’ life rhythms lose homogeneity, coherence and stability. Coronavirus has triggered all of these. In his research titled Cultural Trauma, The Other Face of Social Change, Piotr Sztompka writes, "One possible use of the concept trauma is to deal with the problem of negative, dysfunctional, adverse effects that major social change may leave in its wake, the ‘trauma of change’ inflicted on the ‘body’ of a changing society."

Symptoms of culture shift trauma run parallel to other types of trauma, resulting in depression, withdrawal, disorientation, denial, increased anxiety, paranoia, more frequent and intense emotional reactions, self-harm, violence, suicide, etc. These are the results of the perceived loss of agency or feeling out of control. Trauma caused by culture shift has an unequal effect on various segments of society. Approaches for treatment and recovery need to be culturally adapted in light of vast research revealing that the experience of trauma is culturally determined.

Varied cultural interpretations of the coronavirus crisis

Cultural communities do not share the same interpretation of social categories related to COVID-19 such as crisis, sickness, health, safety, social distance, etc. In the Amazonian city of Pucallpa, where I worked in an extremely impoverished community for one year, the hospital was commonly understood as the place people went to die. Healing rested more in the hands of local curanderos, healers. While concepts of sickness, healing, and crisis may be less extreme in more Westernized business contexts, significant variation still exists and needs to be understood to ensure clear communication. In the Cultural Approach to Crisis Management, the authors remind us that “an individual’s cultural background and understanding of another’s culture guides them to interpret a social phenomenon and respond to the event. People of diverse organizational, ethnic, or religious customs or experiences have distinct understandings and behaviors in crises and emergency situations. Therefore, cultural understanding and adaptation is necessary for effective crises and emergency management.”

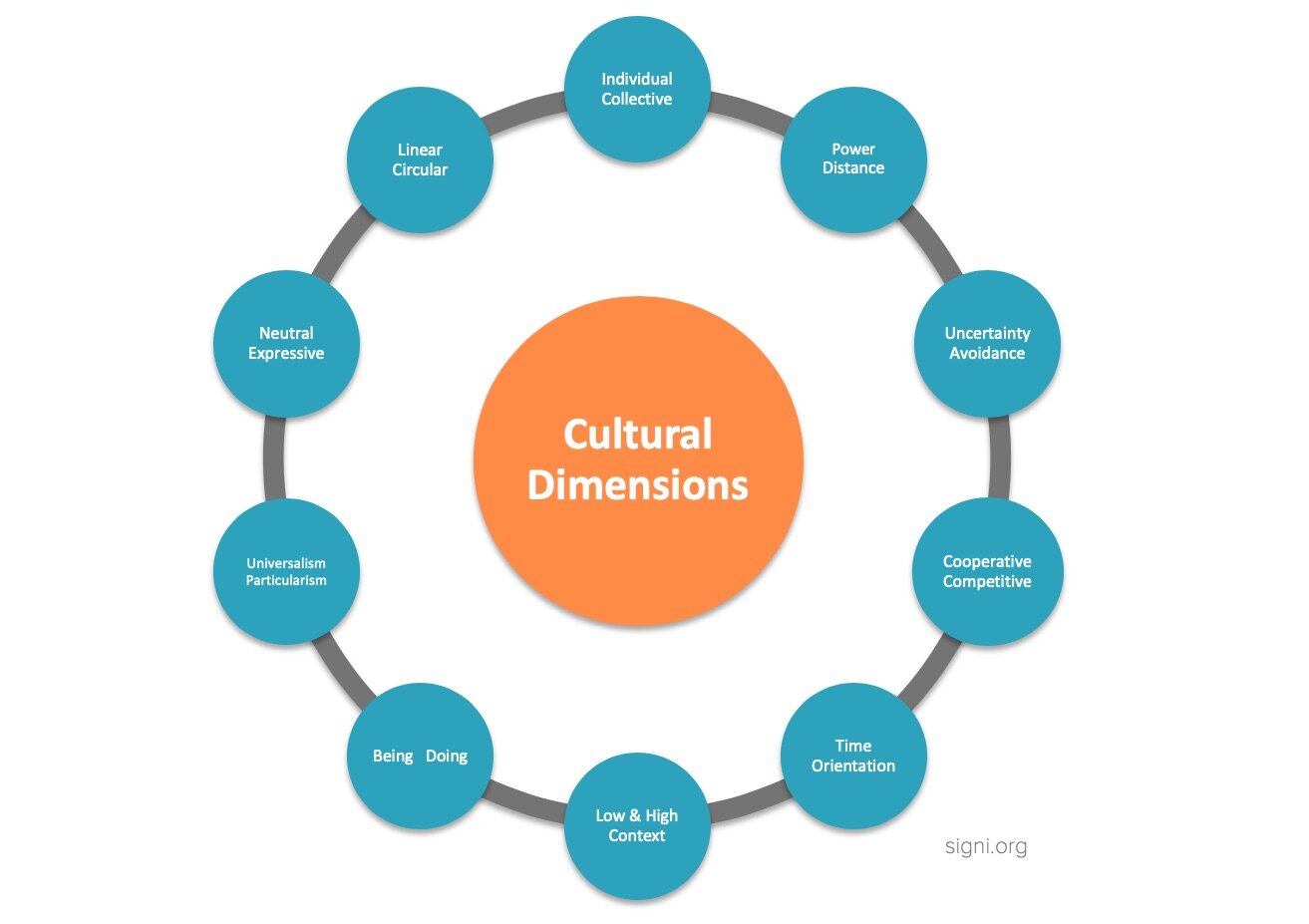

Vinita Balasubramanian, intercultural consultant for Mercedes Benz and contributor to this article suggests that “on a macro-level, organizations might move away from a globalized mindset. On an employee level, attitudes to returning to 'normalcy' might vary. Hofstede's low uncertainty avoidance cultures may be more willing to take risks when going back to work (e.g. ignoring hygiene regulations) than high uncertainty avoidance cultures. High power-distance cultures may accept management decisions regarding transition more easily than low power-distance cultures. Polychronic cultures may show more agility in coping with shifting goalposts.” Overall, Hofstede's cultural dimensions that Vinita refers to offer a highly intuitive and practical approach to recognizing and interpreting cross-cultural behavior. CQ assessments offered by companies like Signi Consulting® discover where stakeholders land on these core cultural dimensions and compare them against thousands of other professionals across ten major cultural blocks.

Cultural regression

In times of stress, people gravitate to that which provides most comfort and the strongest sense of safety. In diverse populations, this likely means an intensified return to core cultural norms. This is not a negative behavior by any means. But organizations that manage multiple cultures will need to empathize with and adjust to this human cultural phenomenon. Annette van der Feltz, consultant at Signi® and founder of Expatriate Assistance, said that “during periods of stress and uncertainty, we tend to resort back to our own culture. In other words, organizations with a multi-cultural staff may see that their employees have temporarily lost some of their intercultural communication abilities. It is important to recognize this trend and learn to manage employees who are displaying these tendencies.”

Coronavirus prejudice and xenophobia

Xenophobia is the fear of people groups outside of one’s own. Annette van der Feltz also reminds us that “during periods of stress, we look for scapegoats, others to blame for our misery. With the virus coming from China, we are already seeing that anyone who looks remotely Asian is at risk of experiencing discrimination, even violence. It is important to recognize and create awareness that this trend is happening, so it can be stopped.” The New York Times pointed to the double threat that Chinese Americans face. They write, “Not only is the Chinese-American community grappling like everyone else with how to avoid the virus itself, but they are also contending with growing racism in the form of verbal and physical attacks. Other Asian-Americans also suffer a bigotry that knows no difference between Asian nations.”

Disease can hit humanity from anywhere. And while globalization offers economic and educational benefits, the quick spread of contagious disease is also a consequence of global interrelationship. Blame cures no one. Instead, nations and communities need to learn best practices from various cultural sources to defend against such health threats.

“Blame cures no one. Instead, nations and communities need to learn best practices from various cultural sources to defend against such health threats.”

I also teach a high school class that includes cultural intelligence training to international students. At the early stages of the pandemic, while we still met in the classroom, I asked students to share their thoughts about the virus. I appreciated the voice of one Chinese student who wrote, “Facing the virus is not a struggle between people, but a struggle between the virus and all lives. This is a war that is 3.8 billion years old, and which humans have not been able to win. So, whatever skin color you have or place you come from, you should not be considered an enemy. Just because most of the sick people have the same skin color, why should they have to withstand violent abuse? We don't need to be blindly tolerant, but we need to look at ourselves from the perspective of others.” I couldn't agree more.

Organizations need to understand the degree to which their community experiences acts of prejudice or heightened insecurity. They need to openly call out misinformation, stereotypes, and degrading discourses, while simultaneously passing accurate and empowering information to all stakeholders.

Organizations must also work to instill cultural sensitivity. Educators need to be particularly sensitive to students for whom trauma can be more highly formative and who often hide abuses for fear of retribution, increased stigma, or shame. A study by Hooker et al. reminds educators that “extensive research tells us the fears in the early stages of an outbreak will soon pass. But the effects of xenophobia and exclusion on those who suffer them may last much longer. Disease stigma can take a toll on a young person’s self-esteem and identity as well as make school environments feel unsafe.” Organizations also need to treat stakeholders who have suffered through the coronavirus with complete respect, making sure not to stigmatize them in any way. How an organization treats their sick is a measure of the health of their organizational culture.

The most current intercultural crisis counsel teaches organizations to know their people. Study them. Do not hesitate to take surveys of focused groups to assess felt needs. If nothing else, talk regularly to diverse stakeholders to get a read on what they are thinking and feeling. Read from sources that reflect insider perspective, and anchor decisions in the frame of reference of the most vulnerable publics. I appreciate the word of Sandra M. Fowler, President of SIETAR USA, who writes, “Just as we know to wash our hands and maintain appropriate social distance, we can promote embracing and valuing diverse people and communities. And we can start with ourselves.”

When relating with people from different backgrounds it is normal to experience difficulties in understanding and empathizing with their experience. Communicating effectively across cultures is an aptitude developed over time. The more we engage intercultural relationships with self-awareness, curiosity, and adaptability the more we will grow our cultural intelligence.

Applying Cultural Intelligence to the COVID-19 Crisis

Cultural intelligence (CQ) is a person’s ability to successfully build relationships, communicate and adapt across national, ethnic and organizational cultures. Because of the diverse makeup of most work environments, SHRM recognizes CQ as “the essential intelligence of the 20th century.”

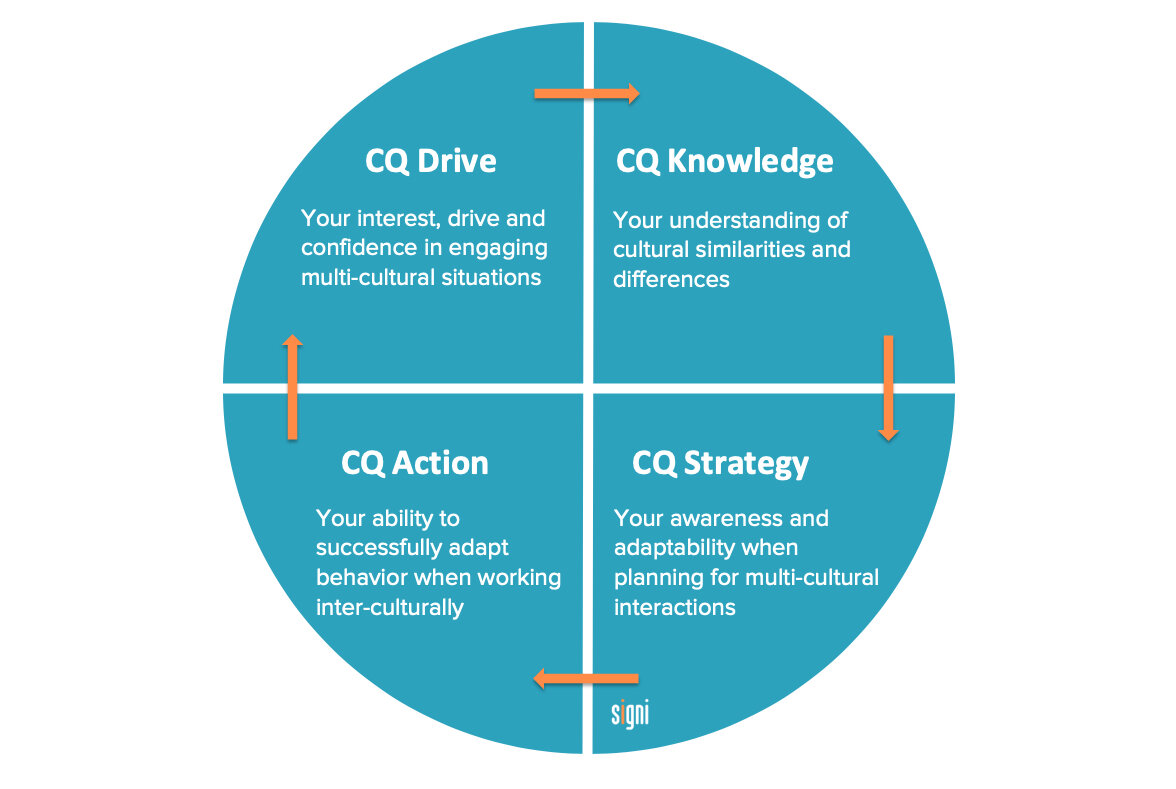

Cultural intelligence is not only an aptitude, but also a researched-based, cognitive measurement like IQ or EQ that can be assessed. It is unique, however, in that it measures capabilities learned through group social interaction. Since no one can possibly master the nuances of every culture, CQ gives a framework or model for learning and behaving that can be applied across all intercultural situations. The framework revolves around the four CQ capabilities of drive, knowledge, strategy and action.

CQ Drive

Drive is your interest and confidence in engaging new cross-cultural situations. Motivation is key. There are two general categories of CQ drive, intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic motivation might include one’s love for novel experiences and unconventional relationships, or it could be a fascination with the limitless adaptabilities of the collective human mind. Extrinsic motivation may include a raise in pay for an international assignment, a wider social network of diverse friends, the superior results of a diverse team or the financial benefit of a new international market.

Most people experience a combination of motivations. But if drive is stifled through fear, ethnocentrism or prejudice, cultural intelligence stops dead. What is your motivation to grow cultural intelligence within your organization? What stands in the way?

CQ Knowledge

Knowledge is discovery. It’s finding the nuts and bolts of something new and figuring out how the pieces fit together. It’s also learning how to read new cultural maps and interpret unfamiliar road signs. Perhaps the most revealing aspect of a culture is its language. But don’t assume that language meaning is consistent among broad language groups such as Spanish, English, French or Mandarin. It’s not. Word meaning is determined by context and habitual, creative, ever evolving usage. Many cultural communities speak English, but their English has adapted to very different environments and histories. Languages, like other technologies, get honed to the best uses in various environments and infused with fresh, contextually relevant meanings.

For shorter cross-cultural engagements, learning some phrases, basic etiquette, and a bit of the country's background will demonstrate your interest in and respect for that cultural community. For longer term engagement, greater fluency in a language along with deeper awareness of family, government, educational, organizational and economic social structures are key. Foundational social frameworks vary greatly across cultures, and there are no silver bullet solutions to intercultural challenges. Also, be careful about showing off your cultural knowledge too soon or it can come across as silly at best, offensive at worst.

What do you need to learn about the various cultures of your stakeholders so that you can safely transition them to post COVID-19 norms? How will your company lingo shift and adapt to change in ways that your organizational community can clearly grasp and re-communicate? How are you co-creating new language, structures, and values together in the broadest sense with your community, especially with the most important and often most forgotten segment, your end-users?

CQ Strategy

Knowledge without strategy is like water without a bathtub. Strategy sets useful parameters that channel knowledge towards cohesiveness and problem-solving behaviors. Strategy applies our higher-level thinking skills to diversity management. It’s your ability to put the pieces of new cultural knowledge together.

Our current context will demand quick strategy creation. McKinsey & Co. says that “responding to the twin challenges of a public-health crisis and an economic downturn may require a new playbook, rapid innovation, learning, and adaptation. But in this highly fluid environment, the public and private sectors alike will need to adapt and innovate, learn what works and what doesn’t, and adjust as they go.” Most strategies now will require significant adjustments along the way and plenty of openhandedness. Shifts might include changes of your end user or a complete reinvention of your product or service. For example, Dyson, most commonly known for vacuum cleaners, has switched gears to develop ventilators.

CQ strategy involves planning, awareness and checking. Planning for the unknown is obviously tricky business. Culturally intelligent individuals don’t assume they know, but they are confident learners. Setting the groundwork is a matter of researching and gleaning from similar situations, then stepping out with the most grounded, educated guesses. Once in the action, awareness of limitations and other’s perceptions of your approaches will help you pivot towards the greatest perceived value for your end users. Following a cross-cultural engagement, checking which techniques led to expected positive results against those which failed assures even greater accuracy for the next round of engagement.

The key for this interim transition period is solving setbacks related to coronavirus. Right now, people won’t be interested in your top ten tips for throwing cool company parties. So, we need to find out which of our services and marketing strategies are no longer culturally relevant, then pivot to those which help our clients’ transition. For B2B, this might mean converting to online platforms or tapping into new markets. For consumers, staying safe, sane, entertained, and productive through increased isolation will be key. Shifting from the tub metaphor to the hydroelectric dam, consider which knowledge is going to spin diverse people’s turbines and get the power flowing in empowering, mutually profitable, life-giving directions.

CQ Action

So, the meeting has been called. The diverse voices have been attentively listened to and penned on the whiteboard. Now it’s action time, the fourth dimension of CQ. The golden rule here is going to be: do unto others as they would do unto themselves.

5 coronavirus CQ action steps

1. Create awareness around CQ

Everyone knows that “others” are different. The challenge is figuring out why in positive, well-grounded and eye-opening ways. If we choose to shift our default people-think from stereotypes, suspicion, judgement and avoidance to a disposition of curiosity, thinking the best, human discovery, and intercultural relationship building, fears will subside and the boldness to confront the unknown will rise. Instilling awareness of global and intercultural opportunities will inspire hope, meaning, and motivation throughout your company. Providing the right tools through cultural intelligence training will assure that you’re stepping out confident and prepared.

2. Discover your cultural signature

Every organization has its own set of values, behaviors, and language. These include a mix of intentional company culture, orchestrated by leadership and the cultural variation that stakeholders bring with them. I refer to this unique cultural makeup as a cultural signature™. A company’s cultural signature differentiates it from competitors. It positions your organization to achieve what others cannot, but only if you are aware of these cultural attributes and what they mean within a shifting market.

I appreciate the emphasis of Thomas et al. who describe CQ as “a system of interacting knowledge and skills, linked by cultural metacognition that enable people to adapt to, select, and shape the cultural aspects of their environment.” The key word here is shape. We have agency during culture shifts. But it takes knowledge of cultural building blocks and cultural intelligence to shape our environment and move past feelings of powerlessness and organizational stagnation.

3. Accept ambiguity

Remember, this organizational season is about pivoting. It’s about quick movement from one uncertain reality to another. I think of the Wright brother’s history of airplane innovation. Lots of crashes. And you know the rest of the story. The willingness to experiment, fail, and experiment again until your vision flies will mark your post-COVID legacy. I realize that grandiose talk of innovation and invention is easier to say than to pay. But honestly, we have no choice. We do know, however, that our cultural relevance will dictate our revenue.

Rather than wait for the market to revive, some local distilleries started pumping out hand sanitizer in response to public demand. One distillery, Litchfield, offered their sanitizer for free, a smart and humane gesture. No doubt, compensation will meet them down the road. My favorite example of timely cross-cultural tech comes from the company, Tushy. When people started freaking out in the empty toilet paper isles, Tushy pushed their portable, self-installable bidets to a wider international audience. They took a fun, punny, humorous approach that resonated with a U.S. market less familiar with bidets. If you opt out of their emails, for example, you’re obligated to click “No thanks, I don’t want a clean butt.”

Vinita Balasubramanian says that “an organization should not remain in a state of hiatus in the current situation. It should accept uncertainty, stay aware of what is going on, learn from it, and create ongoing strategies for dealing with twists and turns.” I find it interesting that uncertainty and surprise are central to both the horror movie The Shining and the Space Mountain ride at Disneyland. The ambiguity is not the problem, it is what we choose to do within it.

4. Keep it human

The most valuable capital for me is relational capital. Personally, I respect people who use their money to build friendships, rather than using their friends to make money. The question here is, how can your company help people through the crisis? Again, deferring to Vinita, she writes, “Above all, as COVID-19 is a human disaster, an organization should remain consistently people-focused and address the human side whether health or financial security–systematically.” It takes skilled organization and high CQ to get the wellbeing of a diverse society back on track following a major hit. Organizational leaders and business owners generally have these skills and should consider how they can invest them in community recovery.

In an interview between Philip McKenzie & Frank Cooper, CMO of BlackRock and former CMO at PepsiCo Inc., Frank teaches us that “there's a function of listening and absorbing, and then translating that story in a way that makes people receptive to it. As marketers, we have to engage in humble inquiry and listen intently to truly understand. It doesn't get more human-centric than that.” In a similar vein, Sharon Hurley Hall, writer and content marketer writes, “You know your business, clients and customers. Ask if you can help. Be on your usual channels but focus on helping people in whatever way you can.”

5. Develop CQ leaders

Every initiative needs someone at the helm to keep it from sinking. Cultural intelligence initiatives are no exception. Because leaders constantly fight against personal biases and business-as-usual routines, your CQ plan needs to form an integral part of your core organizational structure. Make sure that your plan articulates the tangible, context specific benefits of CQ. In his book Leading with Cultural Intelligence, David Livermore points out that “employees can grow frustrated when CQ is simply taught in an overarching ambiguous way rather than customizing its application to specific roles and functions in the organization.” A main part of the plan will be to uncover, assess, and transform various voices into a coherent action plan.

Top leadership needs to be the first to adopt and promote cultural intelligence. Leadership should also put together a culturally adept team to help create and implement your CQ plan and assure ongoing training. Look for people who can make the creative side of your organization flourish. Keep an eye out for natural leaders who are already the trusted go-to for diverse segments of your organization. Invest in those people, remembering that followers define a leader.

In their book Cultural Intelligence, Thomas & Inkson write, “High CQ leaders use group-process knowledge, practice mindfulness in group interactions, adapt behavior to accommodate the unique circumstances of the group, and encourage and train members to become culturally intelligent as well.” I cannot stress enough that a culturally intelligent leader looks for a wider range of viewpoints. Consider again Frank Cooper’s recent interview, where he says, “I always seek non-obvious sources for different ways to understand the world and the challenges we face. I pull from science, the arts, and music. Anything that can give me an idea of what is relevant within the broader culture is potentially useful.” Consequently, organizations that invest in training and ensuring creative space for people like Frank Cooper will experience evidently greater success in their COVID-19 transition.

Conclusion

From factory lines to face masks, cultural meanings are shifting. Consequently, the perceived value of commodities and the mediums upon which they are marketed are also in flux. Some good news in the midst of our shared tragedy is that the human race has persevered through countless crises. In response, we have imagined and realized unparalleled solutions to societal catastrophes. We have done so corporately. Our amazing minds, which organize life experiences into what we call culture, has been our strength for a long time, and we’re seeing it play out now through collective global teamwork. Pointing to the imagery of J.R.R. Tolkien, the world (power players aside) is assembling fellowships. And while we mourn our deep losses in this crisis, we need not despair. We have all shared this experience on an unprecedented global level. We have fought together against a common enemy. My hope now is that this common struggle will unite diverse communities like never before, and that by applying our wonderfully specialized talents, not the least being cultural intelligence, we will walk one another safely to the other side.

Shane Treadway is Founder of Signi Consulting. He also teaches religion and social sciences at Rancho Christian High School in Temecula, California and leads their internationalization program. You can learn more about strengthening your intercultural relationships at signi.org and contact Shane at shane@signiconsulting.com

Contributors

Thank you! Vinita Balasubramanianm, David Schmidt (Editor), Annette van der Feltz

References and Further Reading

Avruch, Kevin (1998). Culture & Conflict Resolution. Washington, D.C.: United States Institute of Peace Press.

Drozdek, Boris (2007) Voices of Trauma Treating Psychological Trauma Across Cultures Edited by Boris Drozˇd¯ek Psychotrauma Centrum Zuid Nederland/Reinier van Arkel groep ’s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands John P. Wilson Cleveland State University Ohio, USA© 2007 Springer Science Business Media, LLC

Fast Company. (2020, April 12). 5 creative ways small businesses are succeeding during the COVID-19 quarantine. Retrieved from https://www.fastcompany.com/90489203/5-creative-ways-small-businesses-are-succeeding-during-the-covid-19-quarantine

Marketplace. (2020, March 25). Some small businesses are flourishing during the COVID-19 pandemic. Retrieved from https://www.marketplace.org/2020/03/25/some-small-businesses-are-flourishing-during-the-covid-19-pandemic/

Business 2 Community. (2020, April 13). 24 Marketing Experts Reveal How Businesses Can Survive & Thrive During (or After) the COVID-19 Crisis. Retrieved from https://www.business2community.com/marketing/24-marketing-experts-reveal-how-businesses-can-survive-thrive-during-or-after-the-covid-19-crisis-02301320

European Cultural Foundation. (2020, March 13). Corona Crisis calls for a Culture of Solidarity. Retrieved from https://www.culturalfoundation.eu/library/corona-crisis-calls-for-a-culture-of-solidarity

Inc. (2020, April 17) 10 Ideas to Keep a Great Company Culture While Working Remotely. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/jessica-stillman/10-ideas-to-keep-a-great-company-culture-while-working-remotely.html

Inc. (2020, April 22) To Be More Resilient in a Crisis, Focus on Meaning, Not Happiness. Retrieved from https://www.inc.com/jessica-stillman/to-be-more-resilient-in-a-crisis-focus-on-meaning-not-happiness.html

Livermore, David (2010), Leading with Cultural Intelligence, New York, NY: AMACOM

McKinsey & Company. (2020, April 29). COVID-19 and jobs: Monitoring the US impact on people and places. Retrieved from https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/public-sector/our-insights/covid-19-and-jobs-monitoring-the-us-impact-on-people-and-places

Media Village. (2020, April 22). BlackRock CMO Frank Cooper on Resilience, Purpose & Crisis Management. Retrieved from https://www.mediavillage.com/article/blackrock-cmo-frank-cooper-on-resilience-purpose-crisis-management/

New York Times. (2020, April 1) Covid-19 Changed How the World Does Science, Together. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/01/world/europe/coronavirus-science-research-cooperation.html

Quinn, Naomi, Roy D’Andrade, Holly F. Mathews, et al. (2005). Finding Culture in Talk. New York, N.Y.: Palgrave Macmillan

Silva, Arlene and Klotz, Mary Beth (2006) Culturally Competent Crisis Response, Student Counseling

Star Tribune (2020, April 6) After virus, how will Americans' view of the world change? Retrieved from https://www.startribune.com/after-virus-how-will-americans-view-of-the-world-change/569401652/

Sztompka, Piotr (2000) Cultural Trauma: The Other Face of Social Change, SAGE Social Science Collections, Jagiellonian University, Poland. Retrieved from http://www.lib.csu.ru/ER/ER_Philosophy/All_Schreiber/shreiber2/cultural%20trauma.pdf

Thomas, D.C., Elron, E., Stahl, G., Ekelund, B.Z., Ravlin, E.C., Cerdin, J.-L., Poelmans, S., Brislin, R. and Pekerti, A. (2008), “Cultural intelligence: domain and assessment”, International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, Vol. 8 No. 2, pp. 123-143.

Yeo, J. et al. (2017) Cultural Approaches to Crisis Management In A. Farazmand (ed.), Global Encyclopedia of Public Administration, Public Policy, and Governance, Springer. Pp. 1-4